with the floor staring back at her;

she remembers that time he decided he had had enough of their broken futon and threw the frame out while she was at work. she came home from work that night and saw the new arrangement—she didn’t have much of a say in it. she didn’t have much of a say in anything at all. they had a mattress for a couch; they would eat on the floor, though she doesn’t remember what as neither of them cooked; they watched the gilmore girls in various states of unrest, or at least that’s what she hoped would keep him home on tuesday nights. she doesn’t remember much about what they did for love or for pleasure. the walls were grimy with smoke tar. she sat and waited in that apartment for hours and for days.

written then, rewritten now;

if i loved you before i met you, then surely i would miss you as much.

but how am i to know if there was no wave of an arm, if you never said hello?

i have never meant more than nothing to you, and that is all-encompassing. throwing wish coins into the well of our nonexistence, we revel in our ignorance of one another. our love carries on in busy crowds where elbows graze but do not touch, where breaths mingle with each other but are not swallowed, where our eyes cannot and will never meet.

there is no love as mighty as ours—

silent,

unaware—

and our absence is a testimony to our inessential devotion.

the sidelines;

people walk by and it makes her feel exposed, though no one is paying attention, no one is looking. you walk by, and it’s easy to keep your eyes on the road when you are headed somewhere, when you are in motion. in your passing, in your ambulation, you keep your eyes on the horizon, sharpened and undeviating. your eyes don’t make it to the sidelines, and they don’t catch sight of this blind spot wherein she sits quietly, feeling exposed with her too-dark lips.

she must sleep a while, she thinks.

she needs to watch her heart beat on the other side.

the lines, they remind her of cat scratches, though it’s not because of you, it’s because of her.

vocabulary;

czechoslovakia

every now and then, when my brother and i played hangman, we picked themes. one time, we chose countries. when my turn came, i knew i had a winning country in mind, a country full of the consonants we only guessed at the end, in desperation, long after we had ruled out s, t, r and l. i ran to the bedroom and looked at my pink old-fashioned alarm clock. the numbers had small glow in the dark dots next to them which no longer worked. at the back of the clock, below the lever, was a small inscription: “made in czechoslovakia.” i memorized the letters, ran back to my brother, and wrote 14 low lines on the piece of paper. my brother guessed the word immediately. he had an alarm clock too, only his was black, and it still glowed in the dark.

frisky

i learned that the french word frisquet and the english word frisky meant two different things when, after drinking a lot of wine on a crisp summer night, i told my friend charles i was feeling the latter. in truth, i was feeling chilly; in hindsight, i was probably feeling both.

tryst

i did not know what tryst meant until april 21, 2000, at noontime. i learned the word tryst before i learned the word frisky.

toboggan

there was a young boy, a loner—he got to school early, when the school buses hadn’t yet arrived, and the school yard was still empty. he wore a brown winter suit and spoke like a young french boy. one morning, he approached me and asked me if i liked toboggans. i enjoyed sledding, but in my mind toboggans belonged in martine picture books, and i could never understand why one would use that word out loud, when there were other words that could be used. it was the only question the young boy asked me, and i never saw him after that.

writing/astute

after reading some of the things i wrote, brett taught me that writing only took one t, not two. i was young; he thought i was astute. i thought so too, even though i misspelled writing, and i didn’t know what astute meant until he told me that i had that quality in me. i appreciated his delicate, discerning eyes.

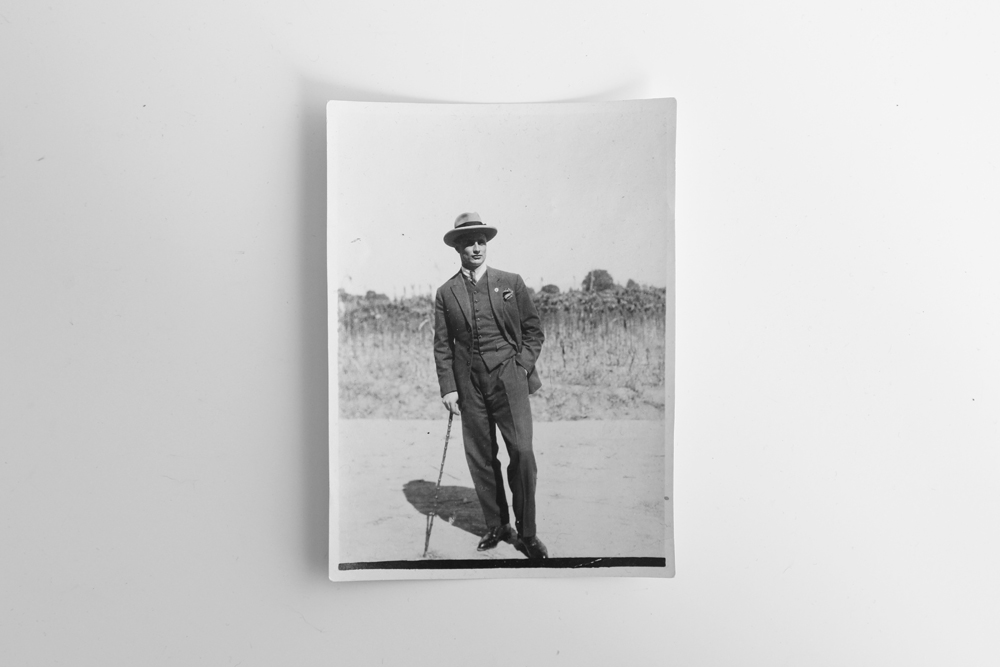

he loved the water;

he loved the water. it made him incredibly happy. he loved the water, but it was dangerous to live so close to the river. he could cross the road and walk to the shore and fall right in. he didn’t know how to swim, the current was too strong, it would overtake him in an instant. he went swimming sometimes, but he always stayed in the shallow end, covered head to toe in orange floats. water brought the brightest smile on his face.

he not only loved the water, he loved all liquids. he could swallow any of them, so long as they were within arm’s reach. he loved pop and fruit juices the most. he even had a short stint with turpentine, though it was short-lived, and he got his stomach pumped immediately afterward. he wasn’t too fond of prune juice, though—even he knew its purpose, elemental.

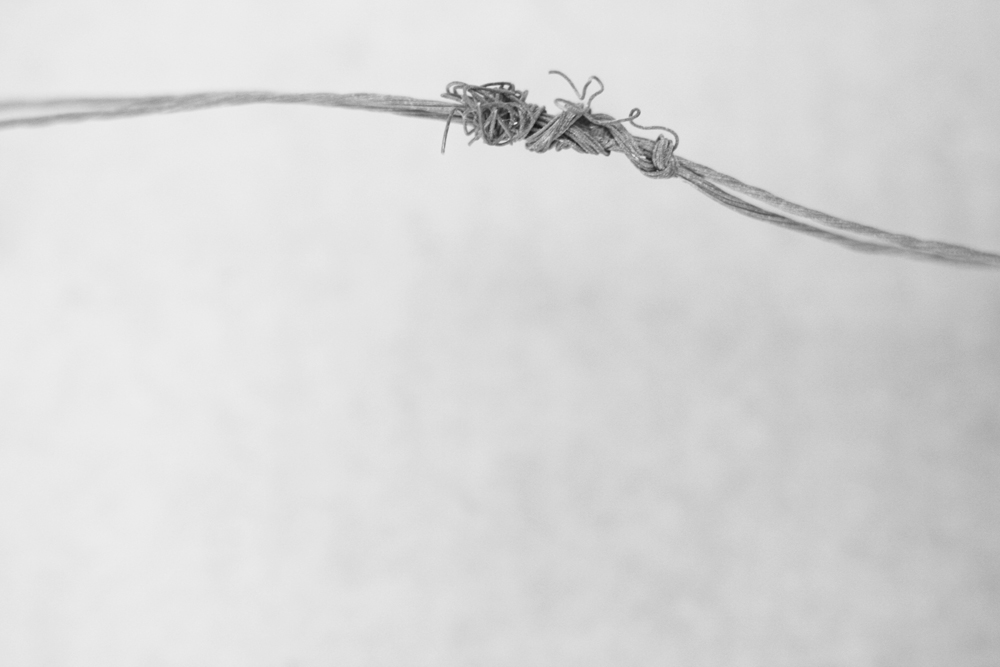

we lost him, once. the latch on the backyard gate was left unhooked, and though the backyard was full of able-eyed uncles, aunts and cousins, we lost him. we couldn’t find him. we thought he might have gone to the river, and we panicked. we knew he would never know how to ask for help. he didn’t have the words. he never knew the words, and only we knew how to interpret his wails. we could be a second too late.

but we found him.

poolside, three neighbours down.

and at that moment we loved him even more than he would ever love the water.

eating habits;

the entire family is sitting down in the living room, eating roasted salted pumpkin seeds. the mother, the father, the son and his wife keep a small amount in their left hand. one by one, they pop a seed between their front teeth and nibble on it until the shell falls off. the salt from the seeds temporarily numbs their bottom lips and the tip of their tongues. their eyes look straight ahead. it is dedicated work with little reward.

when the family stops eating roasted salted pumpkin seeds, their attention shifts back to one another. the mother gets up and walks to the other side of the room. the son starts a conversation with her. the wife sits between them. she wishes the mother or the son would change positions so that she wouldn’t be caught in their dialogue. she looks at her husband, but he doesn’t sense her discomfort. she doesn’t interfere.

the son and the mother talk for a while. the mother finds a few cucumbers to offset the lingering salt. she cuts the cucumbers into four small portions, and the family munches on their slices, looking at no particular point in the distance.

cutting it up;

it’s been a long day.

a day when every gesture seems forced (never forceful); where bridges, cliffs, balconies and rooftops make one beautiful, candid family; where the head pounds, predictable, in a mess of heavy curls.

i missed the beginning of the month.

***

the lycée girls are commenting on a boy, the boy who had just talked to them. they think he is oily. his hair, his face: oily. an adipose sight. l’âge ingrat. they all gather and leave at the order of their teacher.

there is a woman, dressed in black, red haired, faded. all cold fire, burning out. then, two men. brothers in noses. big noses always catch my eye, they get my observation, a note in my book. not small ones. i never see the smalls one. the perfect noses, they mean nothing to me.

an angel cleft, high cheekbones.

people wait for the train.

someone presses on the gas pedal of a motorcycle.

there is the train.