kılı kırk yararak;

the room is unbearably light. the sun might as well be hanging from the ceiling. everyone is so beautiful here. men with dark halos dangling from their shoulders, all beards and noses and thick hands. women with high cheekbones and long, sweeping necks. feet angled in appreciation of fragile ankles. voices made rugged by stories told in cigarette smoke. i abandon myself in us, with you there and me here, but we never collide.

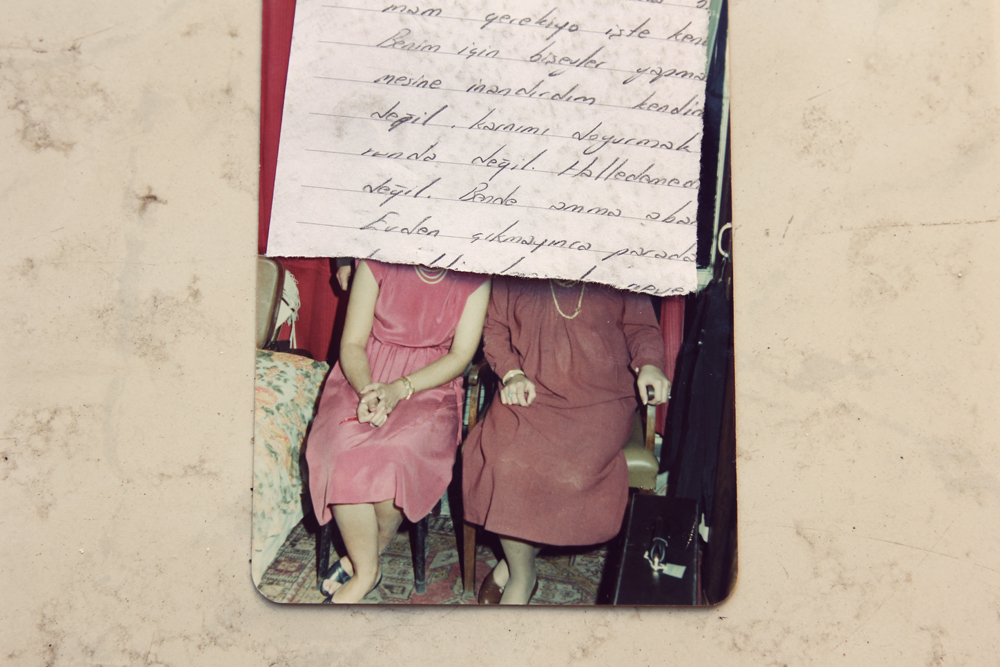

when i was young i used to bring a pad and paper with me wherever i went. i sat in a corner and scribbled and wrote in silence, while people cooked and moved and whispered around me. i was never asked to set my prized instruments aside. i was surrounded by everyone i loved and loved less or not at all; and no one questioned or wondered what i was doing or why i was doing it. it was what i did. i kept everyone at a distance that was safe but not irreverent, and i knew when to pause to wash my face, to help set the table, to water the geraniums.

i had a grey-eyed friend, then. she was a few short years younger than me, and we frequently found ourselves in the same rooms, with the same people cooking, moving, and whispering around us. we couldn’t relate to each other, but we knew that we eventually would, in our shared memories of one another. many times as i scribbled and wrote, my grey-eyed friend stood behind me and braided my hair. i covered pages upon pages with ink; she carefully gathered my hair, let it fall, and braided it all over again. we understood that we would never have long conversations, but together we kept our solitudes company. it was a beautiful thing.